This is a very heavy photo/video-based article, and I highly recommend reading it on the Substack app or website. Email-based readers or social media-based readers will fail to provide you with the correct formatting. The article is too lengthy and will be cut off. Please read it on Substack for the correct experience.

For those who will listen to this article with the AI audio, there are several pictures and videos scattered throughout this article that the AI will not tell you about, and the AI also does not read or make you aware of any non-English text, which means it entirely skips any Arabic text, so do be aware of these small issues in an otherwise useful and fantastic feature of accessibility. Thank you to the listeners who made me aware of this. Going forward, if I include any blocks of Arabic text, I will put a tiny disclaimer at the start so you can be aware before the AI skips it.

In the name of Allah, the Lord of Mercy, the Giver of Mercy

I remember, growing up, going to Arabic school every Saturday. From the age of 5 until 12, I spent seven years in an institution designed to provide me with the tools not only to understand and memorise my religion but also to interact with my culture in a personalised manner, rather than through the intermediaries of translations and our elders. I remember now that I was about five years old when, in the driveway of our home, my parents asked me to recite Surah Al-Fatiha. After a horrible hack at the first verse, “Alhamdulillah (All praise is to Allah),” I was told that I would be enrolled in an Arabic school where they would teach me how to speak. I was devastated; it was as though my world was coming to an end. After what seemed like five of the longest days every single week, you mean to tell me that I had another day of school? Six days?! I wanted mutiny. I probably cried for days until I realised nothing was getting me out of it.

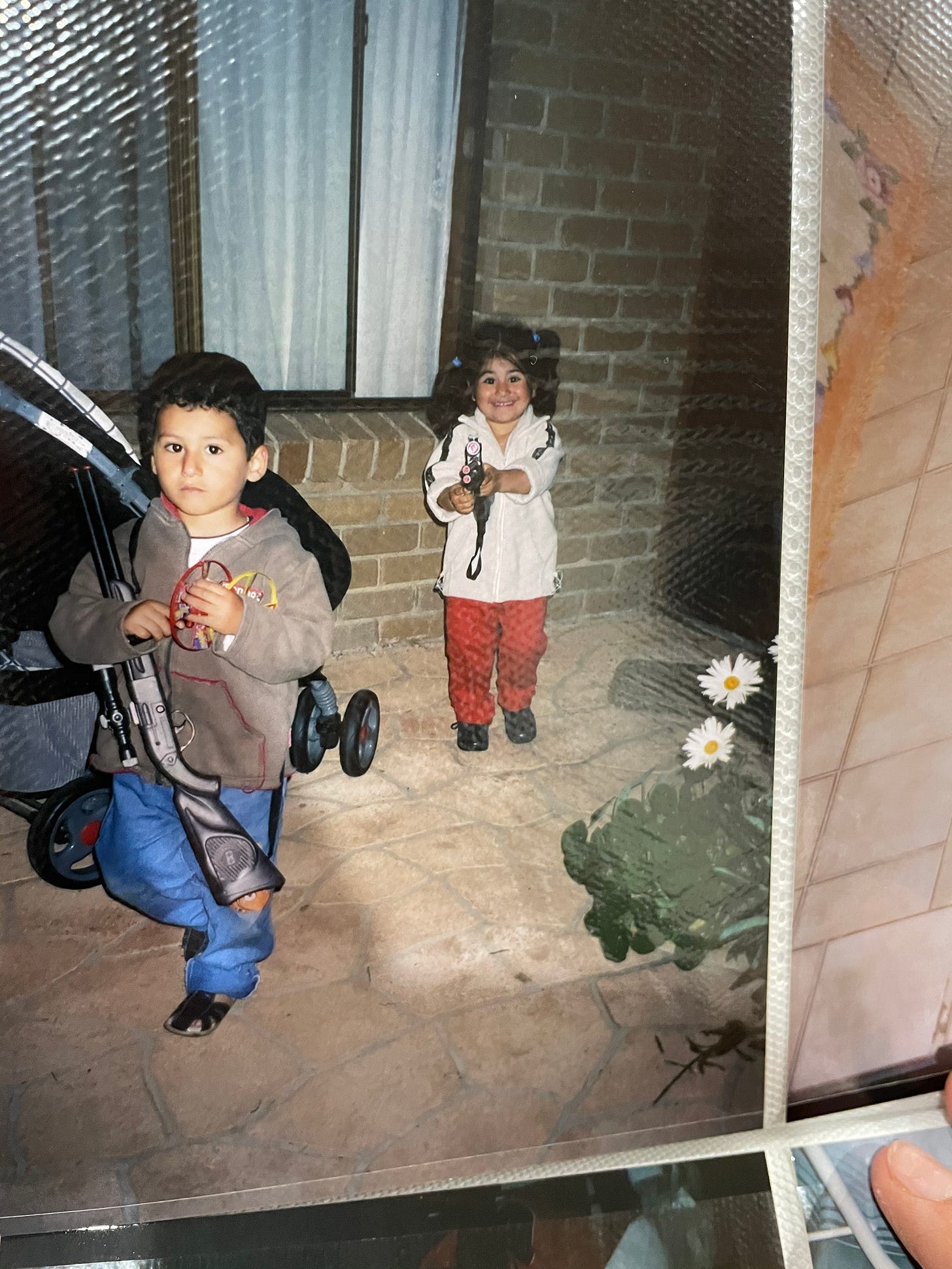

As you can see, I had far greater concerns than another day of school. Primarily, of course, was the struggle for victory over my cousin, who beat me at every game, and I was determined to be better at something. Though I was four months older than her, I lost at every game. Pictured here is me at around four or so years old, plotting victory. That was nearly 20 years ago, in 2006.

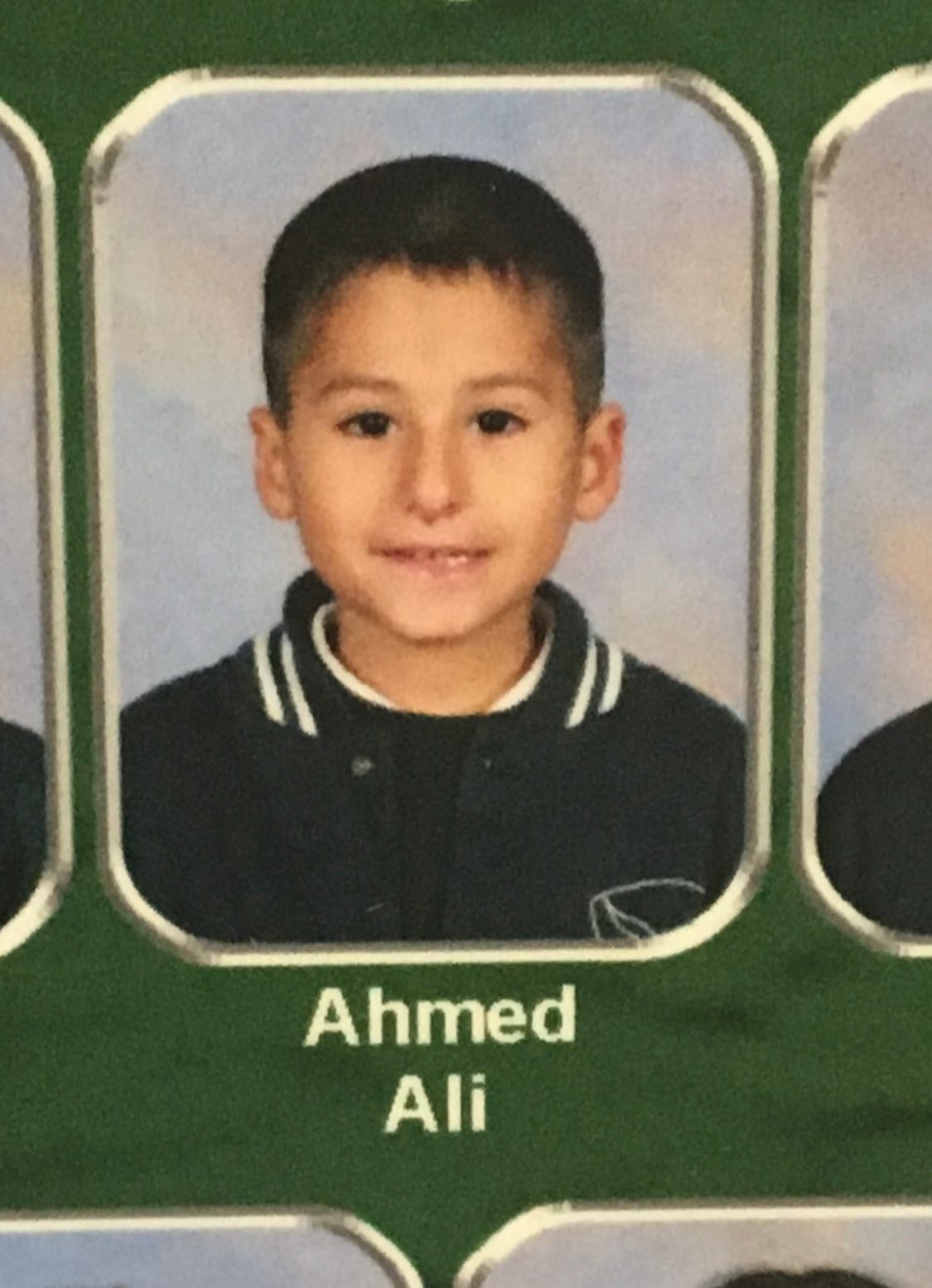

I was in prep during this photo, my first year of school. Not pictured was my devastation at having to go to school for an extra day while my classmates only had five.

I, to no one’s surprise, was a horrible student in Arabic school. I remember even now the feeling I had every single Saturday at 10 a.m. because I knew that soon I would go for my 45-minute break, and, though I did not know until my break, I was certain someone had brought their ball, and we would play soccer. So, from 9 a.m. until 10 a.m., I sat at the back of the class, finding any way to waste time with my makeshift friends of varying ages. Some days it would be “rap battles,” other days it would be our dream 11’s. I, of course, always had Zinedine Zidane in my lineup; he was the untouchable maestri, the composer, the elegant, and the player in my mind every single time I made a touch, a pass, a shot, a call, or a dribble. Growing up, I did not have the same luxuries as I do now to watch a player or a team, and as a child, my soccer knowledge, save for the occasional game replay, was entirely based on the verbal storytelling, the mythmaking, and the idolising. See, I do not think I saw or knew what Zidane looked like until I was maybe 11 or so years old. I heard he was bald. But at six years old, I heard that there was no one better than Zidane, that he played the game as though everything was invented for him, and that the very sport existed only as his symposium.

I remember every single exam I sat for Arabic school, I would either fail completely or get the occasional “good” (جيد), and that was a monumental achievement worth celebrating. My celebrations generally entailed playing near the opponent’s goal, ready to cherry-pick a few tap-ins, or if I was feeling especially elated, I might not do my Arabic homework for a month. My cousins, who I was always compared to, passed every exam with a mark certifying their academic achievements, a “very good” (جيد جدن) written in red on the front page. And so, without fail, I was held back year after year. It took me some four years to learn how to read Arabic because I was so adamantly against it. I just wanted to play soccer, talk about Zidane (a player whom I had yet to see), and see my friends.

Here, I was soon to be six and on a return trip to Lebanon in 2007. From memory, my cousin in the middle, Ahmed (his younger brother Sulaiman in the green shirt), had Command and Conquer Red Alert 2 on his computer, and I was fixated by it. I guess it was the novelty of a computer at someone’s home that captured my attention. I remember wanting to go to their house constantly so we could play Command and Conquer, or rather, watch him play while Sulaiman and I wrestled and replicated the WWE matches we had watched earlier in the day until his mother would interrupt us for food. Even there, we talked about Zidane, Kaka, Ronaldinho, Ronaldo, and, to a lesser extent, CR7 (Cristiano Ronaldo).

Of course, now I wish I had put more effort in; it was an opportunity I would never get again. Seven years of Arabic school for a child should, in theory, and when combined with Arabic exposure at home, which I had plenty of, turn them into a native speaker. I did, however, retain my love for Zidane as my favourite player, and I have committed his biography to my memory as though he were my own uncle. I have hyperlined a lighthearted article on Zidane for those who are unfamiliar and familiar with him alike on this sentence.

I retained some skills I learned in Arabic school, including my native comprehension of the language and my ability to read, but it took many years for me to speak Arabic beyond the limited Arabic I needed to communicate at home, and I still have yet to return to the Arabic speaking skills I had when I spent months at a time in Lebanon, wrestling, playing, and blabbing endlessly about Zidane, John Cena, and the Boogeyman.

Yes, it was not until university that the value of my language and culture truly dawned on me.

At first, I was angry with myself. Oh, how I regretted it. How I wish I had taken my lessons seriously and learned what I now no longer have the same time to learn. I was harsh on myself first, as though, as a child, I should have comprehended the importance of my own culture. But as a child, I was surrounded by my culture and the language in the shape of the adults and my elders; it was ‘boring,’ and playing with my friends was what I wanted to do.

See, what we forget is that a child cannot possibly comprehend the importance of their actions. Though we will eventually gain the wisdom to know what they ought not to do for the sake of their future selves, we cannot ‘make’ them understand us and our adult logic.

Then, in my reflections, I turned to my parents.

There I am on the left, held by my father, with my mother slightly out of frame. My dad would have been around 28 or so, and to his right was his younger brother holding the same cousin who beat me at every game we played, pictured in the first photo of this article.

My father, born in the 1970s, grew up in the far north of Lebanon (the region now known as Akkar), in his village of MishMish, where he worked various manual labour jobs. From a young age, he toiled the land along with his siblings until he was old enough to leave home in search of better work away from his father, at around the age of thirteen. From thirteen, he worked in a few different construction jobs until he was able to find stable work in Beirut with a Christian aluminium factory, where he spent years of his adolescence under their tutelage.

Of course, during this entire time, there was the Lebanese Civil War, whose start and end dates have no consensus. So, at the age of 18, my father was conscripted into the Lebanese forces. After a vigorous training regiment, he was conscripted and placed into the 9th Infantry Brigade (لواء المشاة التاسع).

This patch’s meaning was described by the Lebanese Army as “lightning symbolising permanent readiness and rapid execution, a fist holding the sword of law, and two drops of blood symbolising giving with no limits.” After a year of forced service, my father came to one conclusion: I want out. He did not care whether it was to a neighbouring country or to Antarctica; as far as he was concerned, he had more than his fair share of Lebanon.

After a few years spent in Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia, my father eventually returned home, homesick for a place he had forsaken.

Before I can continue my father’s story, I have to turn to my mother.

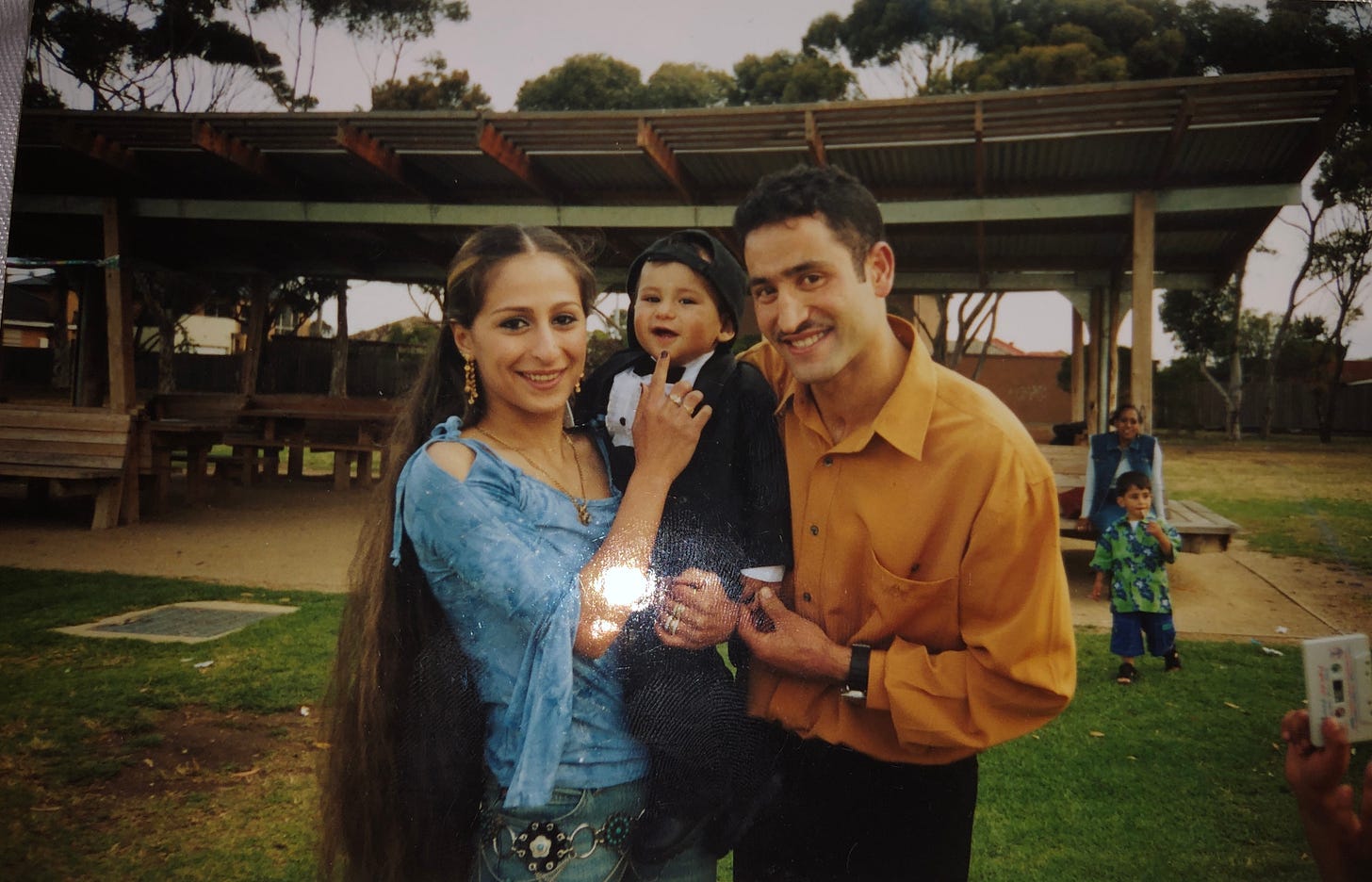

Here I am pictured with my mother, but I do not know why I am wearing a tuxedo. The charm of these photos is attempting to piece together a narrative when your parents have long since forgotten the specifics of each one, and the younger you in the photo is of no help. What a lousy detective I would make! But regardless, this photo was likely taken a year after the one above it with my father.

My mother was born in Baghdad in 1980 to a mechanic father and a young mother. However, thanks to the imperialist nations, my mother and her entire family were displaced as refugees in the 1990s. They spent a year in various Arab states, including Jordan, while waiting for refuge far from what Iraq had become under America’s tutelage by massacre, until they were granted refuge in Australia.

Settling in Queensland first as refugees before moving to Victoria, my mother and her family learned how to hide their Iraqiness in a state that was actively involved in the destruction of their homelands.

My mother, on a holiday to Beirut, met my father by accident because of a car crash, and the two fell in love.

Here I am in what I assume to be the same few months as the other tuxedo photo, pictured with my beloved parents in the early 2000s.

I, after having blamed child-me, who could not comprehend the mistake he was making, turned to my parents. Before I learned, and truthfully, before I humbled myself, I held it against my parents. Was it not them who did not force me to learn? But see, the contradiction immediately leaps at you. Who can be forced to learn? You teach someone the importance of something, but if they do not take it with both hands, then it cannot be you who is at fault.

But still, something felt wrong. Why was it so that I never felt the urgency or importance? Why was it that my parents were okay with this? It was only with time that I learned that my parents were never okay with this. And here is where I realised where the fault truly lies.

For those who have the privilege of being of the same colour and preferred background as this settler colonial state, you may be unaware, so let me tell you some stories. For immigrant families, they are still told today that speaking another language other than English to their child will impede their learning and result in a child who is bad at English and will do worse in their studies. Before I get into the myth, let me go into this more. Let’s study the power imbalance here. You have an immigrant family on one hand who dreams of a life safe from the imperialist powers who feel the impunity to kill and invade as they wish, hoping that their children will not suffer as their ancestors suffered for their land, and on the other, you have a doctor, a representative of health, and the child’s defence attorney (on matters of health), telling this family that their very culture, their very tongue, and their expression with it will harm their child’s chance of success. Imagine the bind you put these soon-to-be parents of a newborn baby into: your tongue or your child’s success. What good parent does not desire for their child except a life better than what they had?

Of course, the notion that multiple languages impact learning is a myth. Linguists have said it for decades, and if anything, people have been multilingual for thousands of years with no detriment to their learning capacity. You need only look at the colonised people of the world’s history pages, who had native proficiencies (when their defiance of the genocide of language succeeded) in their own language and the coloniser’s tongue. The fact is that learning and being exposed to multiple languages as a child increases their learning capacity and provides them with better tools to express their emotions. You need only see how children can learn sign languages much sooner than vocal speech, and you will see the child express itself in sign in articulate and expressive manners far sooner than a speaking child will. And yet the sign-language child will also learn speech when the time comes if they are able, and they will excel better as they have already been ‘speaking’ for a long time prior to their vocal capabilities.

So, we know that children can learn multiple languages with no problem, yet why does the advice remain the same in 2023? Why are parents of non-English-speaking backgrounds still told that they must speak only English?

To assimilate them into the colony. That is all. The child will learn English regardless and with no difficulties, even if they have not heard a lick of it their entire childhood. My parents, who were told that I would grow up ‘stupid’ if I did not speak only English, feared to improve my Arabic beyond the religious minimum. Though they could never assimilate, perhaps, in their hopes, I could assimilate and the state would treat me better than it did them and every other minority identity in this colony.

However, it has backfired entirely on the state. Not only have I not assimilated, but I have made it expressly clear I have no interest in doing so; I will not sacrifice my identity for a genocidal state, and I have no interest in becoming White. Because, after all, assimilation in these settler colonies is just a dog whistle for ‘becoming white.’ The whiter you are, the better you are assumed to have assimilated.

So, this was the family structure. My parents spoke Arabic to each other; my dad spoke in the Lebanese dialect, and my mother had adopted a Lebanese-Iraqi blended dialect so my father could understand her. But to me, they spoke to me in English, and if I spoke in Arabic, I would not have been responded to as a child. My father’s English growing up was lousy, and I remember as a child telling him that it was pronounced toys, not toast, one too many times. So, it was my mother who became our intermediary for a few years; I would talk with them, and she would translate it to him until his English improved.

So, there I am in Arabic school, not seeing the value in learning a language that, until now, I did not need to use with my parents in order to communicate my needs and desires. After all, what is language except an imperfect translation of how we feel—our desires, fears, emotions, likes, thoughts, and instincts? Your basic language evolves from the framework of necessities: food, water, sleep, hunger, tiredness, boredom, excitement, and so forth. Until then, I was able to do so just fine in English; there was no sense of need for Arabic.

You see, it is only now, many moons later, that I realise Arabic school was my parents attempt at protest, a way to keep me connected to my culture without them compromising or sacrificing what they thought would be my future academic capabilities. What they had hoped was that I would, in an academic Arabic environment, learn the language without it impacting my ‘English’ learning.

Though it is tempting to say this is the legacy of White Australia, these racist White-assimilation policies remain in place, as it was only a few months ago that a cousin who recently immigrated from Lebanon and who recently gave birth was told the same advice that my parents were told over twenty years ago by the medical staff. It will be this colony’s legacy, but until each and every facet of it is torn down, we will not find in its place a genuine anti-racist society. How can an anti-racist society exist on racist foundations?

Lebanon, a return, and a plan

After a day and a half into my Lebanon trip, where I had spent it in the Aamara (عمارة) village with my grandparents, I was whisked away to return home. Aamara, which was closer to the major cities and on a valley (سهل), was easier for my elderly grandparents’ healthcare needs than the mountainous and distant village of MishMish, in the northern mountains of Lebanon. My trip was spent in equal parts between MishMish and Aamara, with the occasional trip to Tripoli (طرابلس).

On entry to my home village of MishMish, you are greeted with a large blue sign that reads “MishMish welcomes you” (مشمش ترحب بكم).

And my, what a welcome it was.

Driving in, I immediately understood what I had failed to understand as a child. It was there, in the mountains, that I first felt so strongly regret over my Arabic-speaking skills.

It was when I saw the same mountains my ancestors had seen for generations that it made sense to me.

You see, seeing your home as an adult is far different from seeing it as a child. As a child, it was another place to play. I had connections to it, but it was a connection no stronger than my connection to the pitch on my Arabic school’s grassy oval, where I had scrapped my knees an uncountable number of times attempting a dribbling technique an older child did effortlessly.

But here, seeing it as an adult, I understood. I understood that I had, until then, lived a lifetime in displacement, a lifetime away from where I was meant to be, and a life spent in isolation is a life spent longing for something. It is to live a life distracted, constantly wondering, thinking, speculating, and hoping that you will wake up the next day and find that the life that has passed you thus far was but a dream, and you will wake up where you were meant to wake up.

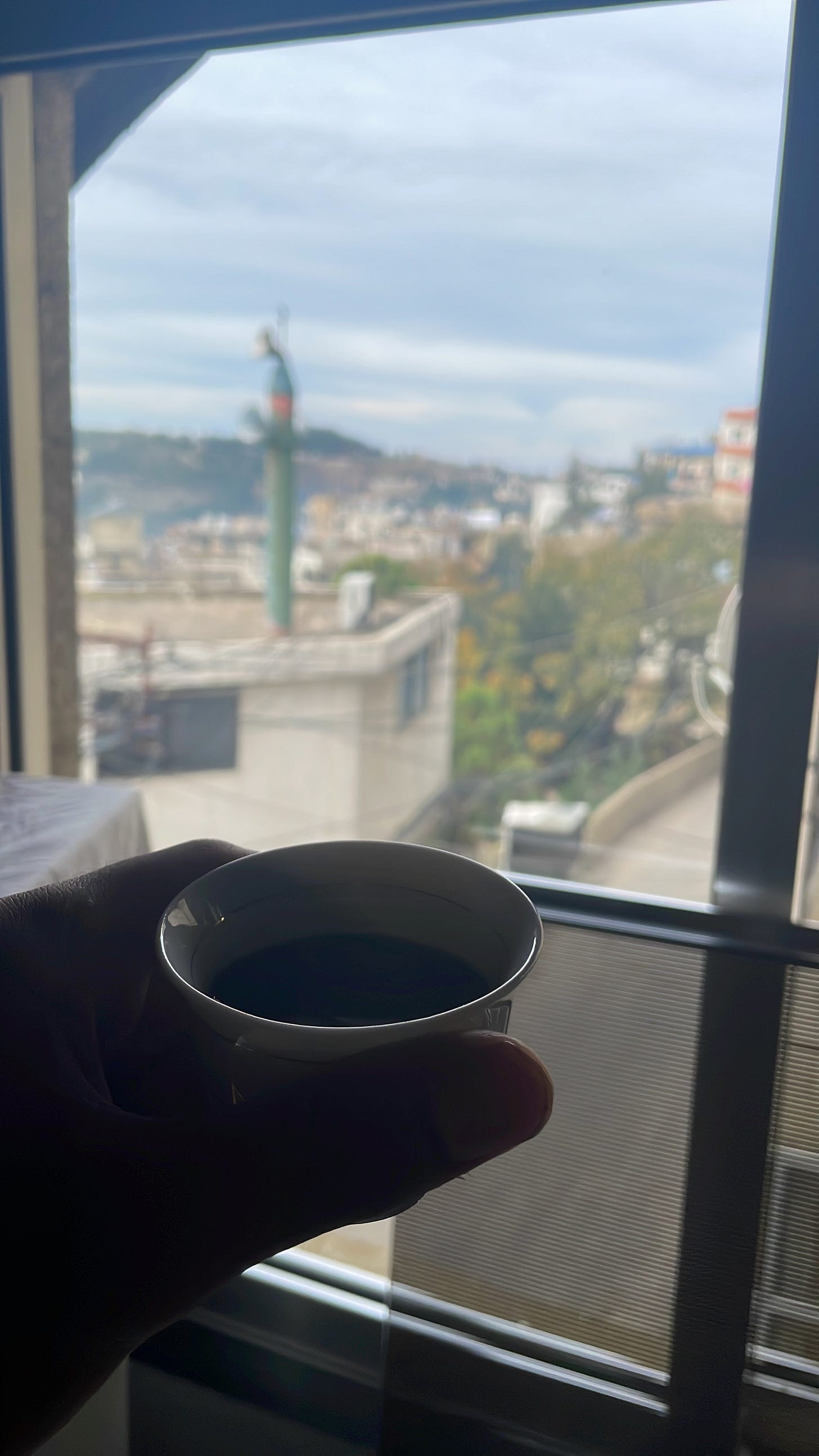

Here, where my first greeting was a coffee and cigarettes, the latter I turned down at every offering in favour of the coffee, I made up my mind immediately. I would give it all up—the life I had lived until then and all its privileges and safety—for a lifetime where my ancestors toiled, lived, died, and were buried. There, when they had long passed, they would provide the earth with the life it needed to sustain future generations. This was the cycle that, until my father, had continued uninterrupted for centuries.

You see, when I say it is where I am meant to be, I do not mean, just in the literal sense, that I wish to be there right now. No, I mean I wish to forfeit what has gone in favour of what could be—a lifetime spent home.

It is how I imagine many of our ancestors reflected as they aged. All we plan, devise, dream, and think, and yet one cup of coffee, a scent, a breeze, a certain angle on a sunrise, or a passing conversation shatters the reality we have become so comfortable with.

It is terrifyingly impressive how, when met with immeasurable beauty, whether it be a person, a homeland, or a plan, one can so rapidly decide that this is where they must be. It is to say: forget the delusions I had planned prior; this is the truth.

Wherever this or that is, I must be.

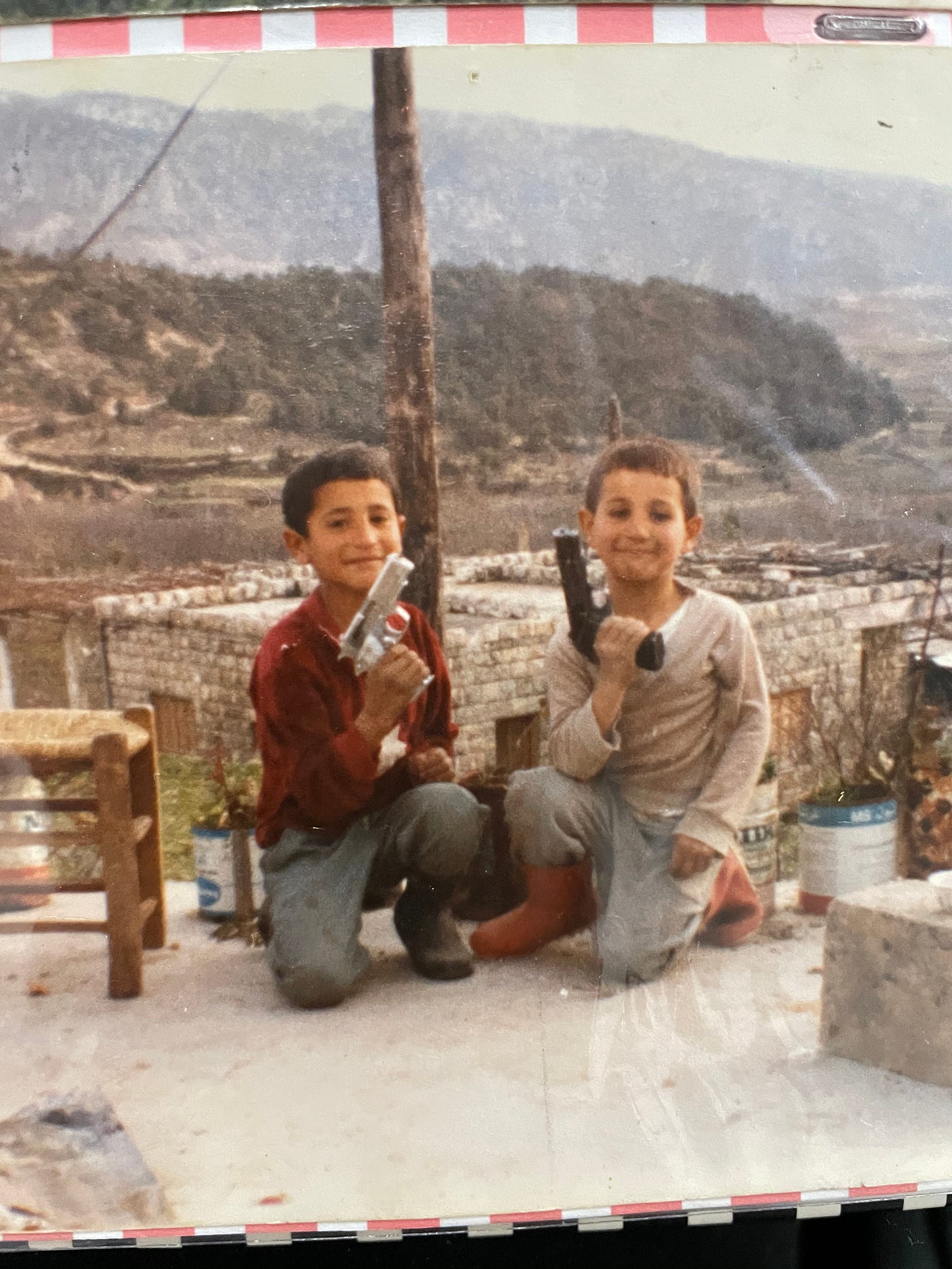

Though I did not photograph it as it was when I visited, I looked upon the same hills and mountains in this photograph of my father and his younger brother when they were still children. In fact, I stood in the very same spot they kneeled on and compared the differences. Where they stood had once been the roof of the family’s shared apartment, but at present there are another two floors built on top of where they once stood. The home behind them had been demolished, and in its place, three separate family apartment complexes stood tall. The road had remained as it was, and the mountain looked exactly the same.

The word surreal did not describe the sense that, some nearly fifty years later, I was standing in my family’s home, the same one my father grew up in and his father grew up in, and so forth.

Though I did not grow up in the home, it made room for me and welcomed me as one of its many lost children. Welcome home, my son.

For many of my mornings were spent like this, with a cup of coffee and the view of a village of people whose histories have sustained this village for centuries. Opposite me was a minaret speaker, and so without fail for each scheduled prayer, the Adhan beckoned me to rush in seek of my Lord’s bounty and success. Was there no clearer evidence of this bounty than to have returned home?

It was there, surrounded by the mountains and the greenery, that I felt so strongly about what I had failed to understand as a child; I belonged there, and without it, I was no one.

But of course, Lebanon does not wait for anyone; our homelands grow and move away from us in our absence. Much like a river, you will never return to the same water again. MishMish, for those who do not speak Arabic, means apricot. Our village, which has not grown apricots in commercial quantity for centuries, has retained a name for a place that was. Yes, it was once the village of apricots.

Therein lies the fear of many who live in the alienating distance of diaspora; the longer we wait, the less it will be recognisable. Much like Zidane, whom I had come to know through stories and mythmaking as a child long before I could ever see him, Lebanon had preoccupied the fantasy section of my imagination; it was a land where my father came from, and my understanding of it was limited to what my father’s family described it as. It was a nation that was simultaneously beautiful and ugly—a nation that stunk yet had the most beautiful breezes. What I understood Lebanon as, or rather, what I could understand it as, was limited to the storytelling abilities of my elders. Zidane, whose mythical status was hyped up by the imagination of children who, at each passing of the story, embellished it with another fib, soon became a totality, a player who was everything about the sport and yet not really human nor a player. In this way, when I first watched Zidane play, I could not actually watch Zidane play. Yes, there was a man, and he was gliding across the pitch like an ice skater, but he was not really a man, was he? I watched him, and yet, because of the myth of Zidane, I implanted the stories onto the Zidane I saw. Every touch he made carried a story, and when he would do a pirouette, I could hear the myth a friend told me once: Zidane’s mother was a ballerina, so he was born with the movement of a ballerina. Of course, she was never a ballerina, and Zidane never once went en pointe.

So, when I visited Lebanon as a child, it was not really Lebanon; I had visited the Lebanon of the stories and the myths. I visited my father’s Lebanon, but it was not ‘my Lebanon’ just yet. It could not be my Lebanon until I understood it, until it made sense to me.

Therein lies the crucial aspect of culture and language for understanding one’s homeland. If you cannot understand it, if you cannot hear the heartbeat of the valley and the breath in the air, if you cannot know the nature, the trees, and the animals that come and go with each season, then you will never realise the connection between yourself and home. You will forever find yourself searching for a homeland that once existed but has long since passed you, searching amongst the tread marks in the dust, left by a car you have no recollection of. You might find specks of tread and rubber in the dirt, but do not mistake it for the vehicle.

And Allah Knows Best

‘See, what we forget is that a child cannot possibly comprehend the importance of their actions. Though we will eventually gain the wisdom to know what they ought not to do for the sake of their future selves, we cannot ‘make’ them understand us and our adult logic.’ Honestly resonates so much with me. I’m Korean, yet I can barely speak it. I was Born in Australia and omg that guilt in not paying attention to Korean schools on Saturdays honestly made me pre upset with myself for a long time. Genuinely I don’t feel like I have a home in a way. I don’t feel connected to Korea, I don’t feel Korean, but nor do I feel Australian. I feel like I’m just stuck in the middle somewhere, but If I had to, I’d call myself more Australian, yet I don’t really know what it means to be Australian. Like the BBQs or the Aussie accent, like I don’t celebrate Australian things. Idk and you as a child just focus on getting better at English because then you assimilate better into the crowd, and fit in. Plus, my English is just a mix of British, American and australian accents. If I just learnt Korean properly, maybe I’d feel more Korean and feel like it’s my home, than a country where my parents were born in. Maybe I’d feel more connected, but idk. Also great writing! Was very engaging and I have ADHD so 🙌

I would love to hear people's thoughts on my latest article, as it is quite different from the others, and I would love to know if this is the style people prefer. Thank you my friends